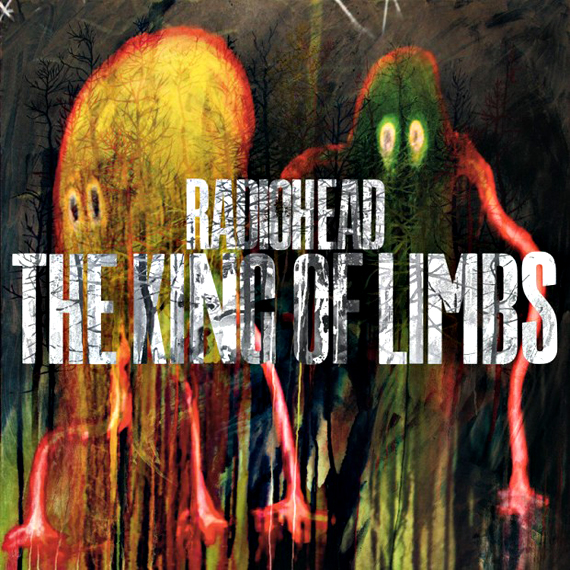

The King of Limbs

by Radiohead

Four Stars

Is anyone either willing or able to define Radiohead’s greatness? I’m not sure very many can. The British five-piece have remained the most enigmatic of shape shifters since the release of “Pablo Honey” in 1992. The albums that followed have managed to elude, in escalating fashion, the comprehensive understanding of their increasingly galvanized fan base. The veiled invitations they’ve extended, to comprehend their labyrinthine efforts, have been a haven for pseudo-intellectuals who’ve foolishly claimed to “know” what Radiohead is “up to”, and for an antiestablishment movement drawn complacently to the band’s effervescent strangeness.

Meanwhile, however, Radiohead ventures forward, putting ever more ground between themselves and the rest of popular culture (their own fans included). Their latest, “The King of Limbs”, released earlier this year, finds a band that will seem, for many, to have abandoned us completely. It is, without question, the band’s most radical effort. It may also be their most inspired.

One must approach Radiohead’s music the way any self-respecting art aficionado approaches any other art form, gauging it first and foremost on the success with which it melds its content and form. Perhaps no other working band has made greater strides with this delicate symbiosis. Their lyrics remain cryptic and confounding, as always they have, with Thom Yorke slurring through the mumbled tones of sexual double-standards (“I’m such a tease, and you’re such a flirt”), leviathanic mystery (“Jump off the edge, the water’s clear and innocent…”), and the band’s habitual puzzling teases (“If you think this is over then you’re wrong…”), but it is the music itself that speaks its own elegant language, and suggests its own function.

Indeed the purpose of “The King of Limbs” is to foster a deepening dialog between the organic tones of the past and the digital sounds of the future, and the narrative of the album’s music suggests an almost apocalyptic, if sardonic, timeline, beginning in frantic clutter, navigating, organizing, and reaching an equilibrium of sorts before collapsing into emptiness, sardonic minimalism and finally, a fleeting ultimatum. Within this narrative are infinite meanings, but again, meanings hardly matter. What matters is that the album evokes a powerful sense of self-contained finality, even as it insists upon its own temporariness.

The album opens with “Bloom”, which is nothing if not a thesis statement for the claims made in the previous paragraph. Opening with a distant piano, the song gives way to a host of what we will henceforth call organic/digital exchanges, the sweet piano offset by a harsh, electronic chirp, a flat, relentless snare drum cadence underlined with a digital drum effect. Soon will come a sterile bass line and Yorke’s curious wale, followed by a band of horns, all of which will disappear into a sampled echo. “Bloom” is the sound of the past and the future colliding.

The ensuing chaos from this collision comprises the following two tracks, “Morning Mr. Magpie” and “Little by Little”, which continue the album’s trend of spastic percussion and conventional instrumentation disappearing into a haze of digital effects. This is, melodically speaking, the weakest stretch of the album for me, but vital to its overarching effect, because after three songs, the album has set a tone, and has lulled us into a rhythm.

What follows is one of the most radical songs Radiohead has ever recorded. “Feral”, for as easy as it is to overlook, is composed of nothing but percussion and Thom Yorke’s voice (at least until a late bass line, but that is irrelevant), sampled, folded, muffled, and twisted into something that is only occasionally, and at best indiscernibly, human. “Feral” marks the halfway point of “The King of Limbs”, and it is easy to look at it and see the organic and digital elements of the album, after three songs worth of chaotic exchanges, beginning to meld into one singular voice.

Appropriately, the most standalone track on the album follows. “Lotus Flower” is the album’s most conventionally composed song, and suggests an organic/digital exchange that seems to have finally found some common ground.

“Codex” follows. It is a massive song. It dwarfs me, and no small portion of its effect comes from what came before. Gone is all of the percussion. Gone are the chaos and the frantic pace. Suddenly, and with astonishing power, the bottom drops out from under “The King of Limbs” and we as listeners are left suspended in an existential emptiness. Amid the clutter, Radiohead hurls us headlong into nothingness, singing “Sleight of hand, jump off the edge…” as if to suggest we’d entered a new world entirely.

To be sure, the album’s organic/digital exchange continues. A distant, metallic ripple descends the scale beneath the song’s mountainous grand piano. It is a small shock when we discover the song uses a common time signature. It employs three-quarter counts and creates a musical tension by drifting between beats. Yorke’s vocals are bold, the song’s chords cold and mythic, not unlike the great “Pyramid Song” from “Amnesiac” a decade ago, but “Codex” is a superior song, because its individual mystery and awe are greater and because it serves a more narrative function within its respective album. There is a vastness to “Codex”, a purity (aided, to be sure, by the album’s uniformly first-rate production value) that renders it something akin to a spiritual experience. It is the high point of the album and the song of the year.

The final two songs on “The King of Limbs” can well be clumped together. Coming in the wake of “Codex”, which is far too powerful a song not to be the album’s climax, “Give up the Ghost” and “Separator” assume a curiously consoling, more intimate tone. An album that had maintained a very high level of deliberate sterility suddenly finds itself in the grip of a very welcoming warmth. An album that had grown in astrological breadth over many songs has imploded. The organic/digital exchanges are behind us. “Give up the Ghost” features only the gentle strumming and patting of an acoustic guitar, and “Separator”, even with a few more instruments, is equally modest. “If you think this is over then you’re wrong,” Yorke assures us. The album may be over, but the music will continue. It always does.

At a meager 8 songs, and covering an equally meager 38 minutes, it is no small feat what Radiohead have created. This is their best outing since “Ok Computer” last millennium. “The King of Limbs” is a methodical, comprehensive deconstruction of the fundamental elements of popular music, past and future. The compositional elements, once reassembled, are discernable and familiar, but the end result seems alien. It is proof that Radiohead are alone in uncharted territory. For all intents and purposes, they are way out in front, paying us a visit from the post-present universe.

No comments:

Post a Comment